Though they may not always be accurate, these “weather influencers” are gaining followers for being available to take questions online.

- A community of weather enthusiasts, who provide hyperlocal weather predictions via X, YouTube, and WhatsApp, are gaining popularity in India.

- In some cases, they are replacing government weather departments, which lack the manpower and funds to focus on making localized predictions.

- They make assessments based on publicly available data and their own findings. Some also have dedicated setups to observe changes in weather.

Elderly villagers in India remember a time when a designated person from the community would climb up a nearby hillock, peer at the sky, study the clouds, and predict the weather. Shyamappa, 84, recalls making such predictions for her village Alagawadi, located in the southern state of Karnataka. “I was correct about half the time,” she told Rest of World.

This enthusiasm for making weather predictions has now gone digital, with easy access to weather data and technology. A network of young “weather influencers” across India is predicting the weather for specific towns, villages, and even neighborhoods — and then sharing updates through social media or WhatsApp groups.

Some have even gained government recognition. In the July 2021 episode of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s radio broadcast, Mann Ki Baat, he praised the then 24-year-old IT professional and weather influencer Sai Praneeth for helping farmers in Andhra Pradesh with his timely weather updates in Telugu.

“It might be raining in one neighborhood but the one next to it might be dry,” K Srikanth, a Chennai-based marketing professional and weather influencer, told Rest of World. He posts updates on his blog, and on social media platform X via his account @ChennaiRains. Srikanth, who grew up in a small town near the coastal city of Puducherry, began taking an active interest in weather patterns after Cyclone Thane hit his hometown in December 2011. He has since gained credibility in local groups as a weather predictor and analyst.

Weather data is collected globally by using satellite information, aircraft sensors, and on-ground observations. It is then organized and put in the public domain by weather data generators such as the Global Forecast System, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, and the India Meteorological Department (IMD). Though weather influencers consult these official sources, they told Rest of World they also observe weather patterns on their own.

“We observe, we have experience, and we understand,” said Srikanth, who has set up a personal weather station at home to measure local temperature, relative humidity, pressure, rainfall, wind speed, and wind direction. A mobile app connected to this station sends him real-time data. The whole setup cost him around $60, Srikanth said. He often gets requests from event organizers to confirm weather predictions ahead of outdoor events.

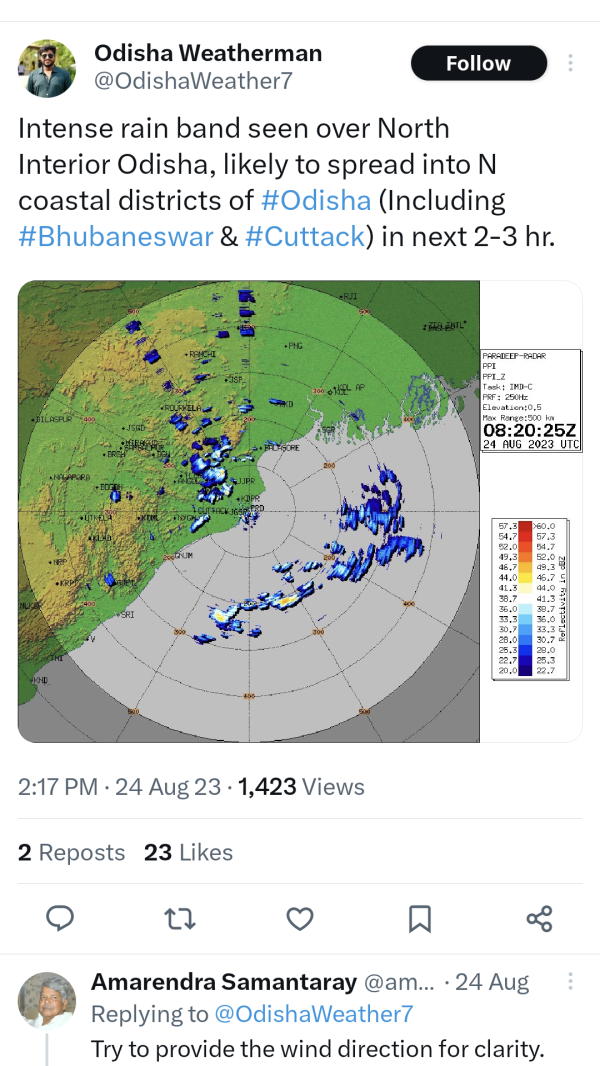

“We need to join the dots between macro events such as El Nino and the depression in the sea right next to our region,” Biswajit Sahoo, an oceanography student who posts on X as Odisha Weatherman, told Rest of World. “It is not about reading the numbers at all; it is about keeping track of the patterns over a longer period of time.” Sahoo said he looks at data shared by the meteorological departments of countries to the east of India — Thailand or Bangladesh — every night. “This has been my routine since the pandemic years,” he said.

One reason for the weather influencers’ success is their hyperlocal approach. IMD publishes its weather predictions for entire districts, across a radius of hundreds of kilometers, while people are seeking “data that is zoomed in,” Kirthiga Murugesan, a crop-weather modeling enthusiast and a PhD student at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, told Rest of World.

Umashankar Das is a scientist at the IMD’s branch in the eastern city of Bhubaneswar. He told Rest of World the state does not have the manpower or resources to do the kind of localized work that weather influencers do, contributing to their popularity among the public. “If IMD gives out data that contradicts the predictions of the local weather predictor, they tend to believe the local person,” Das said.

Murugesan is testing a weather model that collects data every four kilometers in the Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu. She shares it with local farmers on a WhatsApp group daily and alerts them to changes in the weather patterns. “If a farmer puts fertilizer in his crop and it rains, it is a waste of his money,” said Murugesan, whose father is a sugarcane and rice farmer in Tamil Nadu’s Thanjavur district.

Authorities from Courtallam, a small town in the far south of India known for its waterfalls, often call Murugesan to ask if heavy rain is predicted and if it’d be dangerous for tourists to visit. “If I see that there is danger, I tell them to shut down the waterfall,” she said.

But this can be risky, as not all weather influencers have experience — many on social media do not, Das said. “Since the weather bloggers do not have enough training, they can get their predictions wrong,” he said. “During Cyclone Sitrang, [which hit India and Bangladesh in October 2022], based on the predictions by some amateurs on social media, many essential commodities became insanely expensive.”

Sahoo was only 13 years old when Cyclone Phailin hit the coast of eastern state Odisha in 2013. It caused extensive damage to houses, standing crops, power, and communications lines in his state. “From then on, I began researching weather patterns, monsoon, etc. on the internet,” he said.

Sahoo said he has now gained enough experience to make weather predictions. He shares regular updates on his X account and other social media channels. His followers include farmers in the state who depend on weather predictions for their livelihood. At times, he is invited as a guest on local television stations, where he advises people on how to prepare for upcoming weather events.

Unlike government departments, influencers are able to give immediate responses to those in need. “Twitter [now known as X] was best suited for this,” said Srikanth, who claimed he does not miss a single genuine query he gets on the platform.

“We share extensively within the network,” he said. Sahoo, who finds X’s new policies unpredictable, has taken to WhatsApp to post weather updates. “I have just started a YouTube channel, which lets me use my own language [Oriya] to communicate with my people,” he said.

Published in Rest of World

Published on September 11, 2023

Link: India’s weather influencers are faster than official channels – Rest of World