Writer Rinchin tells stories of people whose voices go unheard

Becoming family: Rinchin – ‘My life changed when I connected with children from marginalised sections’ | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

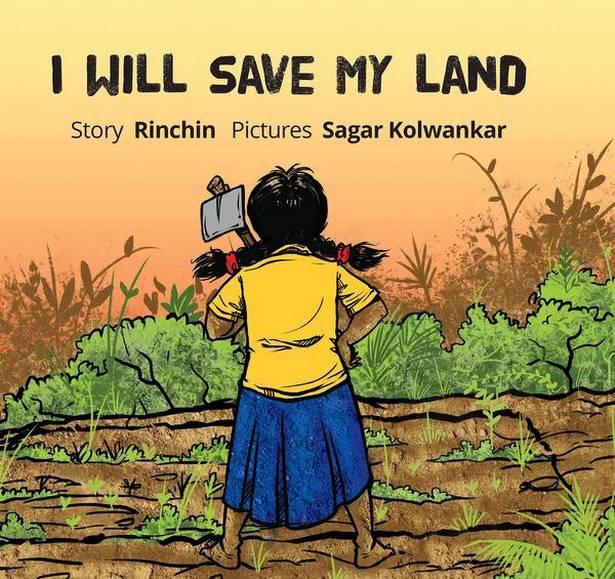

Little Mati pesters her grandmother and father for her own plot of land in the big field. She gets it after much pleading and starts working hard on it. And then she hears that a company wants to dig a coal mine in their village — the enormous black pit that will swallow up all their land as it has done in the next village. The story of Mati and her courage is told by Rinchin in the beautifully illustrated book, I Will Save My Land, published by Tulika. Through the eyes of Mati, Ranchin discusses complex social issues such as caste, class or gender.

Poignant stories

Rinchin, who goes only by her first name, has been debating such issues with the younger generation through her books. For the past five years, she has been documenting untold stories of the people of Raigarh, the coal district of Chhattisgarh, about 250 km northeast of State capital Raipur. “My life changed when I connected with these children from marginalised sections,” says Rinchin. She chose to write about children since she feels they have a larger stake in the way society is going to be shaped. She has already written six books, and two more are in the pipeline.

Raigarh district has one of the largest coal deposits in the country. Industrialist and former Member of Parliament, Naveen Jindal, is said to have transformed the economy of this forested district by excavating ‘black gold’, lighting up millions of homes around the country with the help of thermal power generated from the coal and employing adivasis, so long dependent on forest produce, in the coal mines and factories.

The Jindal story tends to overwrite the stories of the original dwellers of the region. This is where Rinchin, the author of six books set in the region, comes in, recording the tales of the men and women who have lost their lands to the mines, and measuring the impact of the massive depletion of forests on the adivasis’ rights and on the country’s ecology. Rinchin has spent years in rural Raigarh, where people have now become family. “We eat together, work together and struggle together,” she says.

Deeper questions

The inspiration for Mati’s character was one of the young girls in the family she lived with. This girl was intent on performing arduous jobs in the fields that adults felt were too difficult for her. Rinchin says, “The girl kept asking if the land was not hers as well, implying that she should be allowed to work on it.”

In these tribal areas, land is of critical value but not necessarily an asset that communities can feel secure about. The government can take away their lands in the name of ‘larger interests’ at any time.

Often, due legal processes are not followed in the course of such a takeover. Mati’s apparently innocuous query, therefore, about whether the land is not hers as well, raises deeper questions concerning land-ownership and gender.

In 2016, Rinchin published The Trickster Bird, which uses the grandma style of narration to make her young readers familiar with the Paardhi tribals of Madhya Pradesh. Before that, Sabri’s Colours told the story of a Bhil-Barela girl from the Nimar region of Madhya Pradesh who yearns to paint.

Rinchin’s stories are translated into Hindi by her friends. At an event in Bhopal, where Rinchin lives, a girl from the slums came up to her to say that she loved her stories because she could relate to them. But since Rinchin writes in English, her books are read also by children from privileged backgrounds. “The key to a more egalitarian future is to ensure that children from such families are aware of stories of children from less-privileged communities,” she says.

Dying narratives

The tradition of storytelling has remained oral in areas where the levels of literacy are low. “ A lot of stories are lost when the narrators of such stories die,” says Rinchin. In order to preserve some of those for posterity, Rinchin is now helping publish them. A case in point is the charming book by a storyteller from the slums of Bhopal, Chandrakala Jagat. “Helping her publish her stories was one of the most rewarding things I have done,” Rinchin says.

Rinchin has been published by the Bhopal-based non-profit, Ekalavya, and by Chennai-based Tulika. The latter describes itself as a publishing house that cares “not just about a good story but also wants to say something about the wider world, especially current social reality.” No wonder Tulika says on its website that Rinchin is “our publishing gold, completely in sync with our approach.”

Published in: The Hindu

Published on: September 15, 2018

Link: https://www.thehindu.com/books/tales-of-people-forgotten-by-the-development-narrative/article24943661.ece