A reporter makes it personal and finds that young Kashmiris are torn by what ‘azadi’ means for them.

Reporting on fractured societies in Chhattisgarh, Western Uttar Pradesh and Bihar overwhelmed me. I yearned for at least one space to remain violence-free, even if that was only in my imagination. So for a long time, I did not report on the one violent dispute that, in a way, defines India’s identity in the world.

I was determined to prevent conflict from altering my poetry-induced perception of Kashmir. Hence, my first few visits to the valley were limited to trekking on slippery ice-capped mountains, swimming in the Lidder river and hiking in the forests surrounded by lakes. As with most dreams, this too ended when reality struck.

In any case, I believe one needs to get over the visual beauty of the valley before attempting to understand the dark realities of being a Kashmiri in Kashmir. I spent large parts of this past summer in Kashmir reading contemporary political books, speaking to civil society thought leaders over umpteen cups of tea, reporting on a few ‘incidents’ and just… contemplating.

There are as many opinions on the Kashmir conflict, as there are people. But, many would agree that India has embroiled itself in an internal conflict, which it created, and has not the minutest idea how to get out of. I stand with those who believe that this is the darkest phase of India’s relations with Kashmiris since 1947.

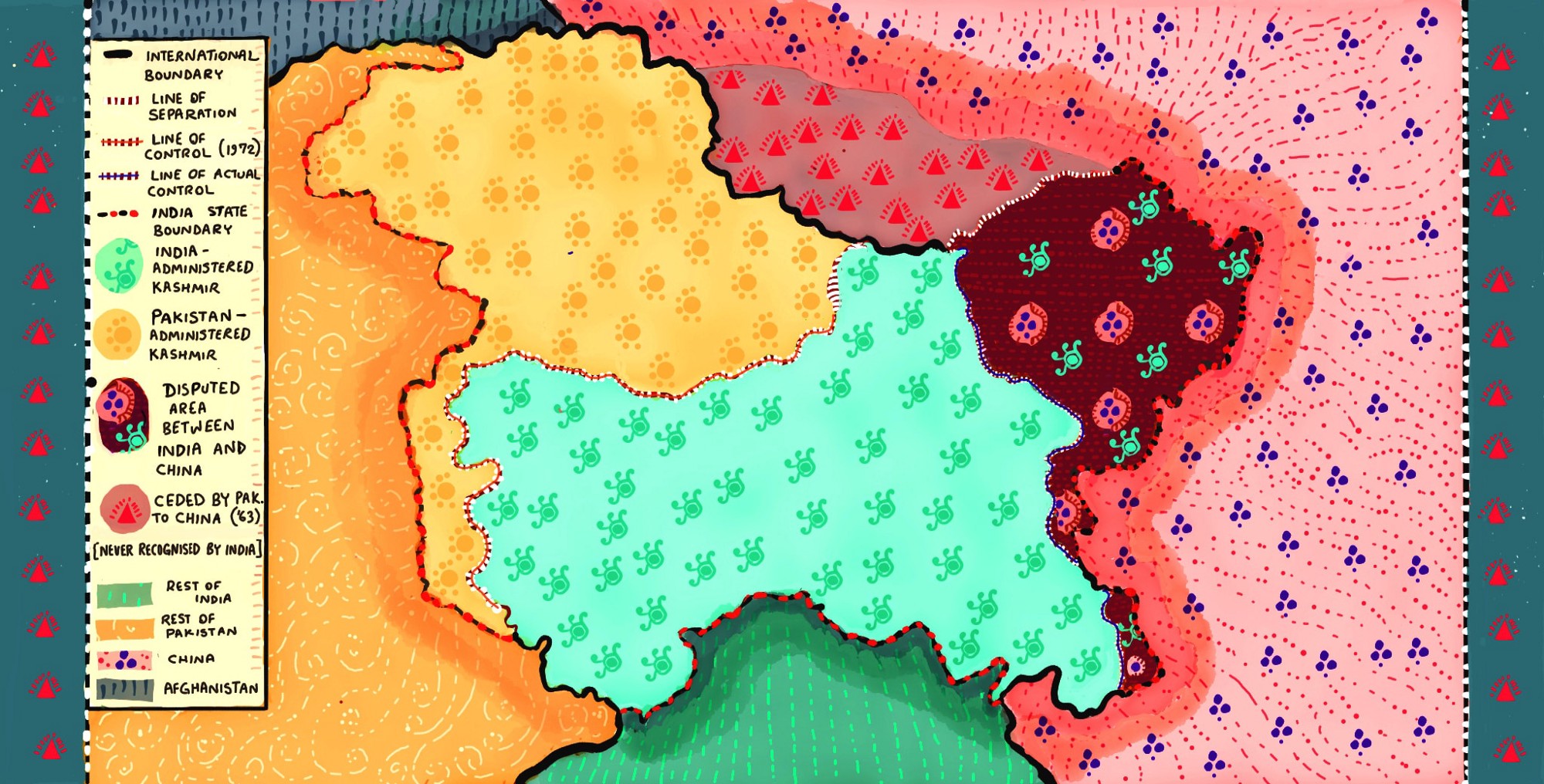

Here’s why: the disputed territory situated between three hostile nuclear nations raises high-pitched demands on its right to self determination. But, without a clear idea of what kind of a society it wants to establish.

Kashmir and India

Students in Indian schools are taught that Kashmir is a fundamental extension of mainland India. “Kashmir se Kanyakumari tak” is commonly used to describe India’s expanse. However, school textbooks don’t contain details of Kashmir’s conditional accession to Independent India.

Indian films, songs, literature and reportage have framed the conflict upon the assumption that the line drawn on the borders of Kashmir is the border that divides India and Pakistan.

We forget that a huge populace that resides between the Line of Control and the southern border of the state of Jammu and Kashmir were promised a plebiscite — an opportunity to choose their futures. We are barely aware of the choice of the thousands of Muslims, Jats and Sikhs of the valley, Punjabis of Gurez, Ladakhis and Buddhists. No one bothered to ask them.

(The matter becomes complex because a Hindu-majority Jammu is geographically linked to Muslim-majority Kashmir. That discussion, though, is for another day.)

Over the past 70 years however, India has created a burgeoning healthcare and education infrastructure in the valley. Most government schools and hospitals in Kashmir are much better looking than their counterparts in, say, Bihar or Orissa. The government (and the army) still provides a large chunk of the employment in the region.

Not to say that all this infrastructure development or job creation is unwelcome. But an average Kashmiri might ask if all this progress can be a reason to reduce their autonomy. By a slew of Presidential Orders, India ensured that Kashmir’s autonomy (guaranteed by Article 370) was steadily eroded.

Kashmiri identity

Even though students in schools in India are taught to think of themselves as Indians first, older residents of Kashmir commonly refer to themselves as both Kashmiri and Hindustani (formulated as Kashmiri pehle, Hindustani baad me). But the younger generation of Kashmiris — who have been educated in larger cities of India and abroad — have an even greater sense of alienation from the Indian state.

Perhaps because they see the stark difference of the state’s attitude towards its citizens in Bengaluru as opposed to those in Budgam. “The first time I saw people stroll past CISF jawans in airports without fear, I was shocked,” a young Delhi-based Kashmiri journalist once told me.

The Kashmiri identity overpowers all other identities of theirs. And they certainly do not refer to themselves as Hindustani. This is what a young Kashmiri lawyer once told me, “I don’t hate you despite the fact that you are Indian”, while narrating the painful story of her brothers’ wrongful incarceration.

It is this generation that will define the future of the struggle. But, like many youngsters across the world living in these fast-paced times, they are uncertain and befuddled.

Kashmiri thought, beyond Azaadi, is obscure

The millennial Kashmiris grew up hearing “hum kya chahte? Azadi”, the mantra of the self-determination struggle, day-in and day-out. But probe a tad further and their thought-bubble bursts.

What does azadi mean to a region nestled between three antagonistic nuclear powers? A well-known lawyer in Srinagar said, “I am with the Kashmiris in their battle for self-determination, but will leave the region the minute they achieve azadi.” He fears the valley is bereft of leadership with a vision. And with a lack of any concrete ideas on azadi, Kashmir might spiral into chaos. Making matters worse than what it is now, which in his words, “might seem impossible”.

Conversations with senior journalists, politicians, university professors and activists all lead to the same answers on azadi. “Let us first get the spaces to demand freedom bluntly,” they say, “and then we can have a more reasoned debate on it.”

For now, what comes closest to the idea of azadi, at least nominally, is Pakistan-administered Kashmir (what India calls Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and what Pakistan calls Azad Kashmir).

However, its Interim Constitution says that the elected politicians should work towards accession of the entire disputed territory (Indian-administered Kashmir included) to Pakistan and that the officials should be Muslim.

Is that what the Kashmiris want? I am certain most of them do not want it. “Islamisation is utter bullshit,” a young Kashmiri tradesman in downtown Srinagar told me. “We do not want a Muslim nation or ISIS, as some of my neighbours harp on. We merely want to live in dignity,” he said.

Being a Kashmiri in today’s times

I sat with a young doctor in the lobby of Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital in Srinagar. After hearing the horrors she had witnessed when those blinded by pellets poured into her ward last year, we sat silent for a while beside each other. Without warning, she looked up at me.

“Do you sing?”

I took a while to answer, “no”. And then added, “why?”

She began a soulful rendition of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s classic:

Kaddi saar ve layi o rab saiyaan

Terey shah naal jug ki kitiyan nenh

Kithe dhons police sarkar dee eh

Kithay dhandhli maal patwaar di eh

Ainj hadaan wich kalpay jaan meri

Jeevain phahee ich koonj kurlaundi eh

(Did you bother to ever inquire, O Lord?

What your subject (man) has suffered in this world?

On one hand, there is the intimidation of police and state

On the other, there is cheating over land and money

My soul is shaken down to my bone just as

The crane caught in the snare, shrieks.)

Unsure of what else to say, I left in silence with a question lingering in my mind.

What would I do if I were in her place? The craving for dignity, respect, equality and fundamental rights that we take for granted in a democracy, makes me wonder how I would react if I were a Kashmiri today. What would I do if I were in living in a city where army trucks line up in an instant; where every innocent stone on the street is a reminder of agitation; where educational institutions are embellishments for more than six months in a year; where opening a grocery shop in a narrow stone alley during curfew is not merely for defiance but for brotherhood; where the internet is as elusive as freedom.

I do not know.

What would you have done?

Published in: NetaData

Published on: 16 September 2017

Link: https://netadata.in/what-do-kashmiri-muslims-want-e0e9bd7a6624