Early last October, the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi made headlines worldwide. By the end of that month, two Indian journalists also were killed—one shot and the other beaten to death. And that’s just a small part of the story for journalists in India: An internationally acclaimed editor was gunned down in front of his office last June. In March, three reporters died within 24 hours when they were run over by vehicles in what were believed to be deliberate attacks.

The killing of journalists—whether by armed militants, right-wing extremists or corrupt officials—is a horrific upward trend in India. As the violence increases, it attracts little attention, and Indian officials refuse to join international authorities in addressing the issue.

The country’s journalists continue to report on corruption and other wrongdoing, but they work amid a cloud of threat, fear and uncertainty.

A democracy is only as good as its media. In this respect, the world’s largest democracy is resting on a dangerously shaky foundation because of the intense challenges that journalists must overcome to do their jobs.

Bloody October

On Oct. 29, Chandan Tiwari was abducted from his village in the state of Jharkhand in eastern India. Tiwari, a journalist working for a Hindi daily newspaper, was found the next day severely beaten in a forest a few miles away. He was dead on arrival at a local hospital.

On Nov. 1, the police identified three suspects in the case. One was a private contractor whose allegedly corrupt deals involving government funds had been exposed in articles by Tiwari. The contractor has been arrested and is awaiting trial.

Since last April, Tiwari had repeatedly urged the police to give him protection because he had received death threats. He never received that protection.

The day Tiwari died, another journalist was shot dead in the neighboring state of Chhattisgarh, where he was covering state assembly elections. Achyutananda Sahu, a cameraperson for the public broadcaster Doordarshan, was accompanying a police patrol when it was ambushed by a leftist extremist group that opposes elections and advocates the violent overthrow of the Indian state.

No arrests have been made for the killings of Sahu and two police officers in that attack.

The central Indian forests where Chhattisgarh is located have seen a violent battle between the state’s paramilitary forces and the Maoist Communist Party of India, which seeks the destruction of the Indian government. These forests are rich in coal and iron ore reserves. While the government encourages private corporations to mine these minerals, the Maoists resist such operations because they want to protect a traditional tribal lifestyle against the onslaught of capitalism.

Three Deaths

The three Indian journalists killed within a day last March were Navin Nishchal, Vijay Singh and Sandeep Sharma.

Nishchal and Singh worked for Dainik Bhaskar, a leading Hindi newspaper in the state of Bihar. On March 25, both died immediately when the motorcycle they were riding was run over by a sport utility vehicle that belonged to Mohammad Harsu, a local political leader.

Earlier that night, the two journalists had gotten into an argument with Harsu over articles written by Nishchal. Harsu had been upset about Nischal’s stories covering child marriage and other topics.

Observers say Harsu often pressured journalists to write pieces that supported him, and he had allegedly made verbal threats against Nishchal and other journalists in the past.

The police arrested Harsu and his son after the incident, but no charges have been filed.

The same day Nishchal and Singh were killed, Sandeep Sharma, a reporter at a local news channel in central India’s Bhind district, was killed when he was hit by a dump truck. Sharma was working on a story about illegal sand mining. (This mining is a lucrative industry because sand is in heavy demand as an ingredient in the concrete used in India’s current building boom. However, sand mining also presents a major environmental threat because it destroys beaches and waterways.)

Sharma’s death created a chilling effect in the region. Closed-circuit TV footage of his motorbike being crushed by a truck was circulated widely among local journalists, inciting fear among them. Like Tiwari, Sharma had unsuccessfully sought police protection. He had received threats after he reported on the alleged involvement of the state police in illegal sand mining operations.

No arrests have been made following Sharma’s death.

Ram Manohar, a freelance journalist, describes the stress—and despair—he and others face as they pursue their work.

“We write about the oppression of … people who live in our villages,” says Manohar, who lives and works in the crime-racked state of Haryana where handmade pistols known as kattas are widely available for less than $5.

“Can you imagine the pressure we work under?” Manohar says. “They (the muscle men in the villages) wield kattas! Our deaths will not even get a mention in national publications.”

Fighting State Repression

Although most of the murders are underreported, incidents involving high-profile Indian journalists have attracted more attention.

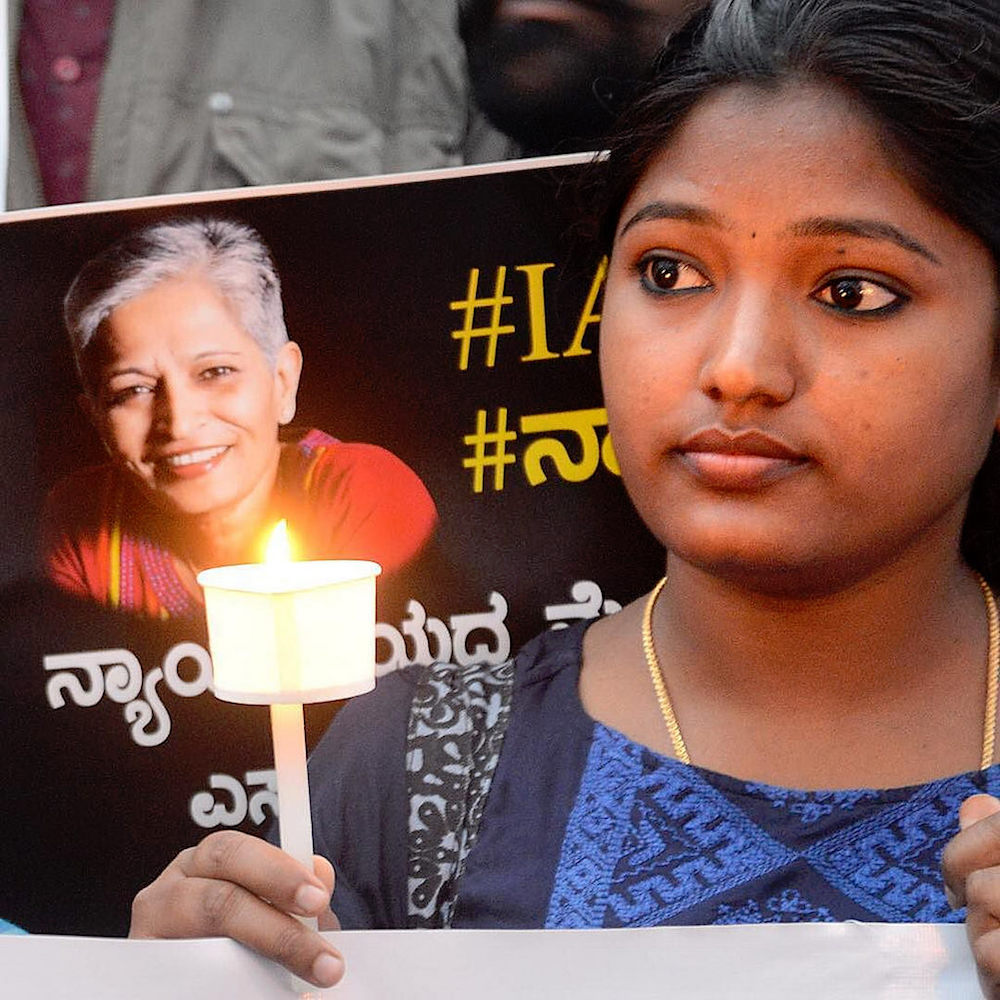

In the course of nine months in 2017 and 2018, two journalists of international repute—Gauri Lankesh and Shujaat Bukhari—were fatally shot.

On Sept. 5, 2017, two men killed Lankesh, editor of the Gauri Lankesh Patrike newspaper, outside her home in the southern city of Bangalore. Lankesh, widely admired for her support of progressive causes, had been a social activist and a vocal critic of right-wing Hinduism.

The Karnataka police initially arrested three members of a militant Hindu organization in connection with Lankesh’s murder. Authorities now believe the killing is linked to a larger conspiracy, and at least 13 more suspects have been arrested over succeeding months.

In June 2018, three gunmen shot Bukhari in front of his office in the northern town of Srinagar. Bukhari, editor of Rising Kashmir newspaper, had survived previous assassination attempts and was accompanied by two security guards at the time of the killing.

Bukhari had supported peace and held balanced views on Kashmiri self-determination, and anti-India militant groups had opposed those views. One of the men accused of the murder was later killed by Indian security forces in a gun battle in Kashmir. The other suspects have not been found.

PEN International, an association that supports journalists and other writers in danger, issued a report on India in September. The report addressed the murders of Lankesh and Bukhari:

Both were targeted for their outspoken views on state repression. Both had a near cult-like following among their readers. Both were in their 50s. And both ran local newspapers in their hometowns, which had extremely limited subscriptions. Gauri Lankesh Patrike and Rising Kashmir sold merely a few thousand copies.

It was clear it was not only their newspapers which were swaying the masses (the two editors were, as well). Their individual personalities, with incisive views on religion, state repression and violence, were immensely influential. Both journalists’ Twitter handles, Facebook pages and fiery speeches in public rallies and conferences were seen as a threat to the powerful. They were attacked by the left and the right; the extreme right considered them to be too liberal and the extreme left thought they were too moderate.

‘Getting Away With Murder’

Compounding the horror of attacks on Indian journalists is the fact that many assailants aren’t brought to justice.

In October, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) released a report titled “Getting Away with Murder: CPJ’s 2018 Global Impunity Index spotlights countries where journalists are slain and their killers go free.” The index deals with journalist murders that took place between Sept. 1, 2008, and Aug. 31, 2018, and calculates the number of unsolved murders as a percentage of each country’s population. Fourteen countries with at least five unsolved murders each were included.

India had 18 unsolved cases in that period, and CPJ noted that the percentage of murders relative to India’s population had worsened since the publication of last year’s index.

Also, last year India failed to participate in UNESCO’s report on impunity, which requests and documents information on the status of investigations into the murder of journalists.

India also fares poorly when additional dangers to journalists are considered. The 2018 World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders weighs factors such as censorship, hate speech and social media threats as well as physical violence against journalists. India currently ranks 138th out of 180 countries (with a lower ranking being worse).

Currently, Indian federal law provides no special protection for journalists, although one state, Maharashtra, passed such legislation last year.

Critics say the law looks good on paper, but they add that its implementation may be difficult because of the political climate and the glacial pace of the judicial system in the state. They compare this law to a similar law designed to protect Maharashtra doctors who are increasingly being assaulted by patients’ relatives. Passed in 2009, that law hasn’t resulted in any convictions.

Media observers also doubt whether laws alone will guarantee change. They say the threatening environment in which journalists work has grown worse since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014. Commentators have said Modi’s nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party squelches dissenting opinions and even tacitly approves of the ominous social media threats regularly directed at journalists.

Journalists’ advocates offer some ideas to improve this dire situation. Proposals include forming an organization dedicated to press freedom in India and creating a legal defense fund to help journalists. Other recommendations involve putting international pressure on governments to protect journalists and using international resources to bolster investigations in cases of violence.

Persevering in the Face of Danger

Journalism in India seldom brings financial reward to employees or owners of publications. Journalists—especially those working for local publications—usually are forced to rely on other sources of income such as soliciting advertising for newspapers.

Many journalists face pressure from their families to leave a field that puts them in harm’s way and provides so little monetary benefit. The situation also puts tremendous emotional stress on family members.

“(When) my husband leaves home in the morning on his moped, I light a lamp for his safe return,” says Radha Devi, Manohar’s wife.

But whatever the cost, many continue to report on—and uncover—entrenched corruption, misconduct and injustice.

“Journalists who work in smaller towns and villages—and those journalists who are working to expose the powerful—are certainly not doing it for money, because there isn’t any,” says Sevanti Ninan, author of several books on the Indian media and founder of TheHoot.org, a website that tracks media developments in the country. “They are driven by the sheer will to build a better society.”

The media is considered the fourth pillar of democracy in India, after the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. That pillar seems to be trembling in the face of the grim statistics of violence and other threats to free expression. However, hope remains among journalists.

“How can [India] give up on trying to build a just society?” says Tameshwar Sinha, 23, a journalist from Chhattisgarh who reports on state repression and gender equality. “We have dreams we want to realize. The only way to do so is to ensure we speak truth to power.”

Published in: TruthDig

Published on: January 8 2019

Link: https://www.truthdig.com/articles/the-lethal-threat-that-hangs-over-indias-reporters/