- In 2006, India passed a law designed to protect the rights of forest tribes who have lived among the trees for generations

- But a Supreme Court decision in February, spurred on by conservationists, could see many evicted unless they prove their claims to the land

Vijayalakshmi Porte’s tribe has lived in the forests of central India’s Chhattisgarh state for generations.

Hers is one of the numerous indigenous communities that live in the heavily forested Antagarh region, subsisting on the resources to be found among the trees.

But despite their strong connection with the land, stretching back to time immemorial, Porte and her people are now faced with the prospect of eviction – unless they can produce documentation proving their claim by July.

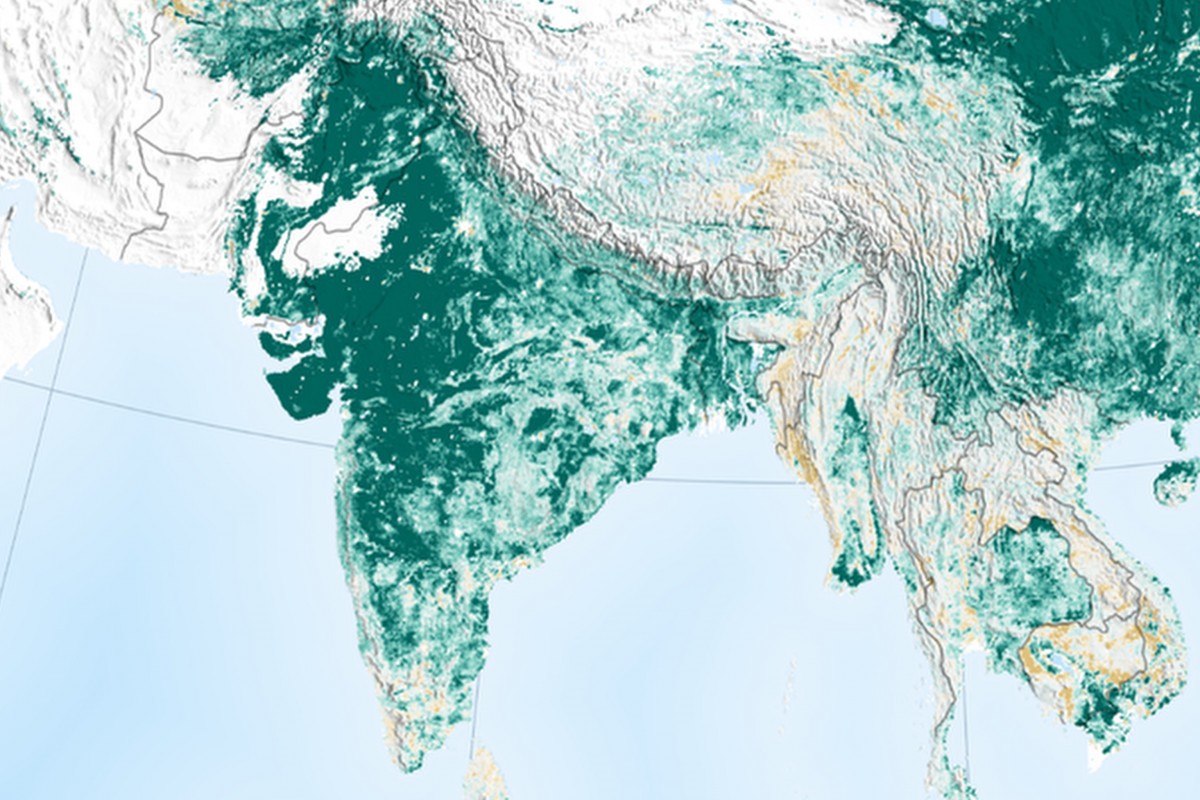

India is home to more indigenous people than any other country on Earth. At the last census in 2011 nearly 104 million respondents – about 9 per cent of the population – were categorised as indigenous.

They occupy nearly one-fifth of the country’s total land area, and are considered by some rights groups to be the protectors of the resource-rich terrain.

Porte’s village of Kondagoan claims about 11 hectares of forest as its own, tended to by everyone in the community.

“We do not believe in slicing up the lands for individual use,” she said. “If we care for it collectively, we will all be taken care of by the jungle.”

In 2006, the federal government of India passed what is commonly known as the Forest Rights Act, a law that was meant to redress historical injustice by recognising the rights of indigenous communities to land and other resources.

In the years since, it has allowed some village councils to assert their claims over the forests that they call home – such as the Dongria Kondh tribe, who in 2014 won a landmark case rejecting a request by mining company Vedanta to extract bauxite from their ancestral lands.

But a ruling in February by the country’s Supreme Court, which came in response to petitions filed by various wildlife conservation groups, has put millions of indigenous people’s livelihoods in jeopardy.

The groups argued that forest dwellers living in protected areas that contain sanctuaries and parks designed to conserve wildlife should be evicted if they cannot prove their claims to the land they inhabit, under the act.

The court agreed and on February 14, ordered 21 states across India to evict an estimated 1.89 million forest-dwelling families, including Porte’s, whose claims had been rejected.

Activists such as Shankar Gopalakrishnan say that these claims were denied for a multitude of reasons – from misinterpretation of the law to incorrect land designation – and not all were necessarily bogus by virtue of being unsuccessful.

He blamed the Ministry of Tribal Affairs for not doing enough to defend indigenous people’s interests, with fellow activist Tushar Dash saying “it’s almost as if the government wanted the act to go away and they were hoping the Supreme Court would do it so they wouldn’t have to face an electoral backlash”.

The Forest Rights Act was introduced by a coalition government led by the Congress party – the main opponent of current Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India’s upcoming elections.

In December, the BJP lost local elections in three states with considerable indigenous populations – Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh – despite many of these same areas having voted for the party in the general elections of 2014.

Opposition parties have criticised the BJP for being weak on indigenous people’s rights, and in the wake of the Supreme Court decision numerous parties and civil society organisations petitioned the government to intervene.

On February 27, under immense pressure, the government called for the Supreme Court to review its decision, which the court agreed to do the following day.

But Porte’s troubles, and those of the millions of indigenous people like her, are not over yet. The court has given the states affected by its order four months to file affidavits describing the process they used to reject people’s claims.

Depending on the outcome of that inquiry, one of the largest land evictions the world has ever known could yet go ahead.

Published in: South China Morning Post

Published on: March 30 2019

Link: https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/south-asia/article/3003953/law-jungle-millions-indigenous-indians-face-eviction-ancestral